Mouth Feel

How to Listen

Listen to any track below just by clicking on it. These are compressed mp3 files. To listen to and download the uncompressed wav or flac files, go to the ThinAirX page on Bandcamp.

The Mouth Feel tracks are sequenced to be experienced from beginning to end, as with a traditional CD or vinyl record. To listen to the tracks without interruption, click here or on the album cover. This will take you to the album player page.

Why it Sounds Like This

Mouth Feel is composed entirely of sounds performed on electrified clarinet. This is electro-symphonic music—electronic technology in the service of compositional ideas borrowed from classical music. It doesn’t sound like most electronic music you hear these days. But it doesn’t sound like an electrified string quartet either. It’s somewhere in between. Learn what I mean by electro-symphonic music on the About page.

All tracks you hear were assembled from excerpts of live performances, recorded directly to stereo. No multi tracking, sequencers, samples or synthesizers. No laptop. These tracks are essentially how I sound in live performance.

The full setup I used to create Mouth Feel. The Eventide units are the ones with the green readouts. Two Infinity loopers on the left.

What is Electrified Clarinet?

When I tell people I play electrified clarinet, they hear “electric clarinet” and assume I mean something like the Akai EWI or the Yamaha WX7. Those are wind controllers with clarinet-type keys and fingerings, but they generate sound only by sending MIDI signals to a synthesizer of some kind. That’s not what I play.

I play a regular orchestral clarinet. Because the clarinet, unlike the piano or guitar, can produce only one note at a time, I run it through a series of pitch-multipliers, loopers, and delays to make it sound like a chorus of instruments. Because the clarinet by itself produces only one timbre—the characteristic woody sound unique to the clarinet—I feed it through a string of modulation effects to generate a variety of tones.

As with all clarinets, my sound originates from the vibrations of a cane reed. Except my clarinet is fitted in with a piezo pickup, a high-quality contact microphone, that outputs an audio signal (not MIDI); it’s essentially the same as a pickup on a guitar. I then route the signal from the pickup through guitar “stompboxes” (effects pedals) to multiply and manipulate the sound. This works amazingly well because, in the last decade, digital signal processing has improved and miniaturized to the point where these stompboxes are really little computers. Each box has the power and features comparable to a full rack of expensive hardware modules from ten years ago. And they sound awesome. The core of my setup is three units from Eventide, the Cadillac of audio processing since the 1970s.

Track Notes

Because my style of music and my instrument are so unconventional, you will enjoy Mouth Feel more if you know something about how these tracks came about. I selected and arranged them to represent the full range of what an electrified clarinet is capable of. They also represent a variety of compositional techniques. Most importantly, I hope to give your ears a musical experience that is rich, thought-provoking, and carries you through fantastic mind spaces.

I recommend you listen on a high-quality sound system and position yourself to hear the stereo separation.

Mouth Feel (18:04)

The title track introduces the pure sound of an electrified clarinet, thickened at first by only a slight delay and chorusing effect. I gradually add layers, first with the looper, then the pitch shifter (which actually adds pitches to the original pitch). Further in, I’m altering the tone of the clarinet with flangers, phasers, ring modulators to the point of being unrecognizable.

This track is structured as a theme and variations form (sort of). The theme, clearly stated at the beginning, is based on a whole-tone scale. The variations aren’t in strict sections, as in the classical form, but morph from one to another, going deeper into electronic fantasy landscapes. As the sound grows more complex, listen for phrases from the theme peeking through the layers. Then in the recapitulation, the theme rings out intact, followed by a coda.

“Mouthfeel” is a gastronomic term referring to the texture of food. Mouth Feel, this track and the whole album, is about textures: juicy sounds, chewy tone clusters, melt-in-your-mouth harmonies, creamy noise, crisp rhythms, gummy textures, bitter accents, piquant blips and bleeps.

Nude Descending a Staircase (4:02)

Nude Descending a Staircase, Marcel Duchamp, 1912

Nude Descending a Staircase is the title of a notorious cubist painting by Marcel Duchamp. It was controversial when first shown in 1912, not so much for the style as for the title. Critics griped: “Nudes don’t descend, they recline.” People were upset that they couldn’t make out the nude in the canvas. It caused so much turmoil, it was expelled from the seminal 1913 Amory Show in New York and Duchamp had to take it home in a taxi.

Whenever I visit this painting—it’s a fixture in the Philadelphia Museum of Art—I relish the energy and movement it seems to generate. I chose this, too, for the historic fact that Duchamp was inspired by the effect of stop-action photography, a revolutionary new technology at the time.

I’m creating my Nude with new technology—pitch shifting. For every note I play, my two pitch shifters output as many as six layered pitches. Every tiny inflection in the original tone is immediately reproduced at some interval higher or lower. I can create some really bizarre effects by sustaining a note on the clarinet and varying the pitch intervals using a foot pedal. You hear these pitch-shift effects as dense clusters of notes moving together. The clusters emulate the overlapping planes of the cubist style in Duchamp’s painting.

Nude Descending a Staircase is structured like a tape college—a homage to seminal tape pieces by Stockhausen, John Cage, and first heard commercially in John Lennon’s Revolution #9 (on The White Album). I spliced together the sections from several recordings I made while exploring the outer limits of my new Eventide PitchFactor.

Fun fact: Near the end of Duchamp’s life, he and John Cage were friends. They played chess together every week.

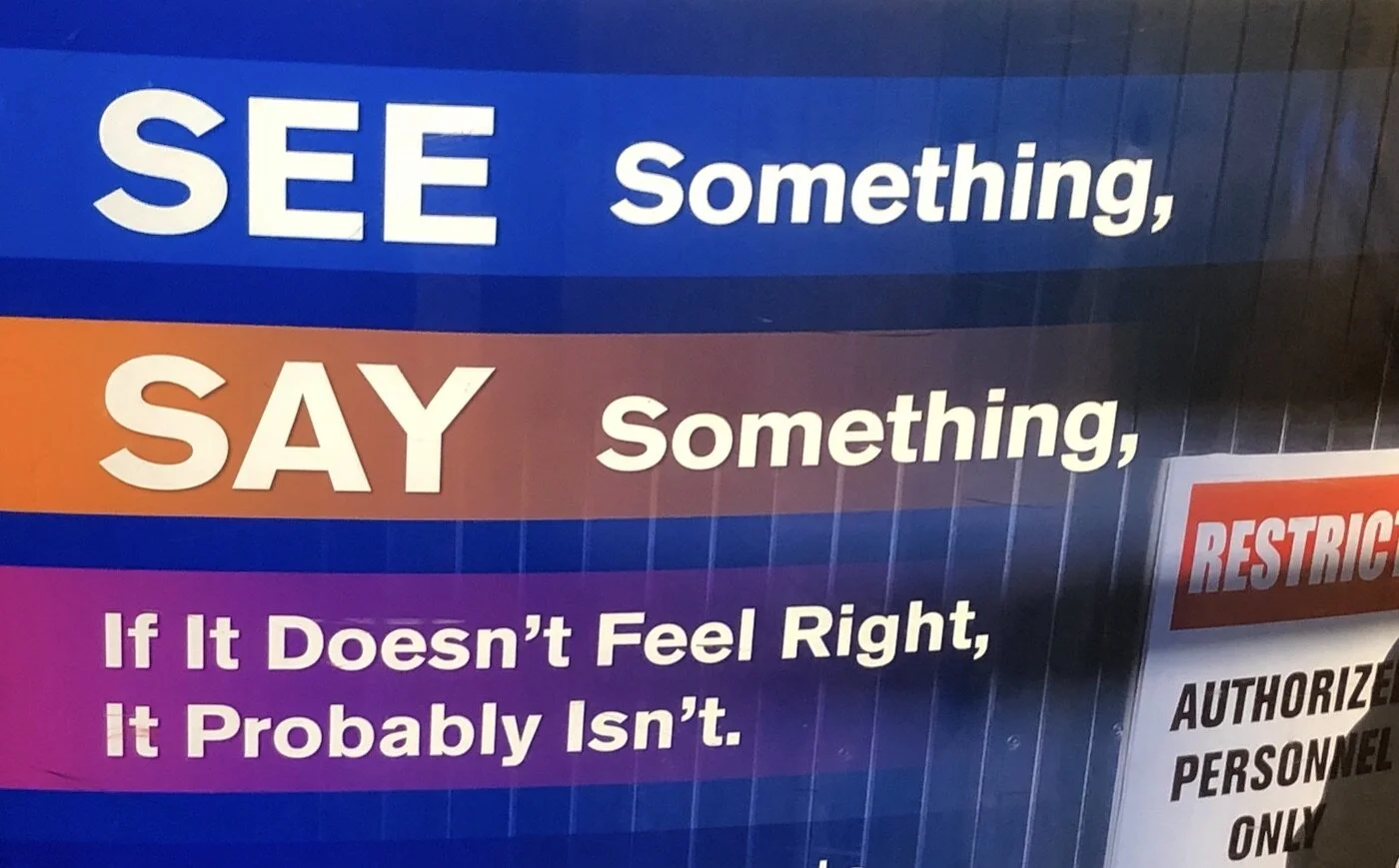

If You See Something, Say Something (8:10)

It it feels right, it probably is.

Every time I pass one of these signs, I chuckle at the unintended double meaning. They’re telling me to be vigilant for bad guys, but also urging me to speak out any time I notice anything cool. Applied to music, I’m asking you do the same as you listen: if you see images, tell us what you see.

I compiled this track from two performances a day apart, and arranged the contrasting sections A-B-A-B. The pulsing sound in the A sections is created with a “hold” function on the TimeFactor delay, switched on and off with my foot.

There aren’t any themes to follow. The point is the contrasting textures.

Be alert, pay attention, and see what you see as the sounds flow by. The coda, the last section, and it’s sweet commentary on the energetic sounds that come before it, is one of my favorite moments.

I couldn’t decide how to end it, so I flushed it down the drain.

Odd Angle of the Isle (11:39)

Ferdinand and Ariel, The Tempest

The title is from a passage in Shakespeare’s The Tempest that describes a lone and dazed Prince Ferdinand taking stock after being washed ashore, fearing he’s the only survivor of the shipwreck, but also just beginning to sense that the island is enchanted. This image fits both the angular atonality and the restless, other-worldly feeling of the music. The feeling comes from the 12-tone row I use to generate all the notes.

A tone-row is 12-note melody that includes all twelve notes of the chromatic scale once and only once. You can hear the tone row clearly as the opening melody of the piece: E, Bb, D, Eb, A, F#, F, B, Ab, C, Db, G. I thicken and vary the sound with effects, loopers, and delays. The row is full of tri-tones (flatted 5ths) to engender even more delicious dissonance as the sustained and looped notes layer over each other. I play the first four notes of the melody as a recurring riff, both forwards and backwards.

The point of using the tone row is to erase the sense of a tonal center by giving each of the twelve tones equal weight. It renders a feeling of being suspended in a harmonic no-man’s land. There is no home key or tonal resting place. Every note is a fresh surprise.

Twelve-tone music is a system of tonal-serialism championed by Schoenberg and Webern in the early 20th century as a radical reaction to the romantic excesses of late 19th century music. Development comes from repeating all or parts of the row in a variety of ways: for example, by transposing individual notes in the melody up or down an octave, or playing the melody backwards (retrograde) or upside down (inverted). But it never caught on and by mid-century became the province of the academics. I’m reviving it now not to be academic, but because I believe it solves a problem inherent in the performance of electronic music—how to create textures of overlapping sounds without succumbing to either harmonic muddle or harmonic monotony. I’m not just creating cool electronic sounds, but sounds chosen from the row, which keeps it interesting in a new way. I’ll continue to experiment with this. You can hear a different, less-strict, early version of Odd Angle of the Isle on Flamed Amazement.

But be assured, it’s not essential to follow any of this theory to enjoy the piece. Just let yourself float with the sounds, marvel at the lush dissonances, feel the Prince swimming in currents of sadness and enchantment.

Open Pit (8:49)

“Wherever we are, what we hear is mostly noise. When we ignore it, it disturbs us. When we listen to it, we find it fascinating.” — John Cage

I agree with Cage. I’m fascinated by noise. I listen for music in noise—for example, the screeching polyphony created by a subway train turning a corner, or the cacophony of construction sites, the spatial movement of thunder bouncing off the hills, the layered sounds of a vigorous white-water rapid. When I do, I practice hearing every layer at the same time, the counterpoint and polyrhythms of noise, from the bass in the low rumbles, to the mid-range bangs and roiling, to the high squeaks and hisses.

Noise, “art noise,” is a genre of music with roots in mid-20th Century classical music, aleatoric experiments, the experiments in computer-generated electronic music, and free jazz from the 60’s. Noise rock bands flourish to this day. The Grateful Dead improvised noise at every show in a segment called Drums & Space. Many people unwittingly enjoy art noise in movie soundtracks.

Most people don’t give art noise any respect. It’s cheating, they say; just make a bunch of noise and call it music. But in practice, it’s hard to do well. There’s a fine line between creating fascinating, ever-evolving layers of texture and detail (good) and spewing a loud, boring mess (bad). It takes experience and practice to do well.

Open Pit is my attempt to make high-quality art noise with only a clarinet. I’m experimenting to see how far I can take it. I chose to feature a ring modulator in my first experiments. A ring modulator drastically transforms the tone by adding prominent and shifting enharmonic overtones. To thicken it even more, I’m feeding the ring modulator with pitch clusters generated by two pitch shifters in series and swept with a pedal. The result is sounds very much like big diesel engines, saws, steel wheels grinding on steel tracks, bulldozers pushing boulders. Delays and heavy reverb adds the illusion of extreme depth, big space—the open pit.

As you listen, see what kind of open pit you hear. Fill it with heavy machinery or monsters or secret fears as you descend into the gaping hole.

Play it loud!

Dona Nobis Pacem (10:24)

I originally intended Mouth Feel to conclude with Open Pit as the last track. But it didn’t feel right to leave my listeners with such darkness. So I conclude with a prayer—a prayer for peace. No dissonance; only consonance. No chaos; only quietude.

The title in Latin means “Grant us Peace.” It comes from the Catholic Mass and has been set to music by composers since Medieval times. My version is built from the traditional, much loved Dona Nobis Pacem melody that is sometimes played at Christmas time; you might have sung it as a round in church or school chorus.

This is not a straight rendition but a recomposition where I tease parts of the melody and float a firmament of suspended tones. It ends with a dance of gentle peace spirits.

An old melody, a perennial prayer for peace, just as urgent now as it ever was.

Ite, missa est.

“If I decide to be an idiot, then I’ll be an idiot on my own accord.”

Gear and Tech Notes

Why the Clarinet

I got the idea to electrify my clarinet from seeing Shannon Hayden do a whole set of electronic music with an electrified cello when we were both performing at an Electro-Music festival. Soon after, I heard more electrified cellos, trumpets, even a flute among the musical avant garde at the annual Big Ears Festival. These weren’t just amplified instruments, but artists embracing the electronics to create new sounds and new music. In late 2016 I pulled my old clarinet off the shelf, added a pickup, and was surprised at how well it worked.

Piezo pickup installed in the barrel of a clarinet. (from PiezoBarrel.com)

What I likeed most is the expressiveness I could introduce into the electronic sounds. The clarinet is naturally expressive, especially when compared to the tones driven by a keyboard. The clarinet tone is driven by breath, but it’s also shaped by subtle changes of lip pressure (embouchure) on the mouthpiece (mouth feel!). Electronic circuitry offers many clever ways to add expressiveness to conventional electronic music, but it’s still mechanical. The clarinet adds a human element to the electronic timbres.

Another surprise when I first started was how big I could make the sound, notwithstanding that the only input is a one-note-at-a-time clarinet. I discovered I could push the electronics and build a continuously evolving wall of sound that sounded like a full synth-driven band. When I’ve had enough of that, I can suppress the electronic weirdness and feature the gorgeous native sound of a fine wooden clarinet.

I’m just beginning to discover all that an electrified clarinet to do. My fondest wish is that other clarinetists follow my example, electrify, and join me in exploring the musical potential of this new genre.

Gear List

Here is a list of everything I used to create Mouth Feel. All sounds originate from the vibrating cane reed of my clarinet. Everything else you hear comes from audio processing and digital manipulation, in real time, using only guitar pedals (“stompboxes”). There are no laptops, synthesizers, samples, sequencers, or pre-recorded anything in the signal chain. This is essentially how I sound in live performance.

Recorded directly to stereo. No multi-tracking. The only manipulation I do in the editing process is cutting and splicing of the stereo tracks (in Logic Pro), with cross fades to smooth out the splices.

Sound source:

Bb Clarinet: LeBlanc Symphonie, 2005 (designed by Backun)

Mouthpiece: Richard Hawkins ‘R’ (this used to be my teacher’s mouthpiece, which he used when he played in the Philadelphia Orchestra)

Pickup: PiezoBarrel installed in a modified clarinet barrel. (No, I didn’t drill a hole in my LeBlanc.) Only available at PiezoBarrel.com

Signal chain:

The audio signal output from the pickup is routed through four stomp boxes in series in the following order. All real-time control is with foot switches and rocker pedals.

EHX Pitchfork (simple pitch shifter; one or two pitches added to the signal)

Eventide PitchFactor (deep and powerful pitch expander; adds pitches to the incoming signal, with options for separate delay and modulation effects on each pitch)

This is a beast. Each of the 10 algorithms changes totally what the pedal can do and how the knobs work.

Eventide ModFactor (tone modulation; separate patches for chorus, phaser, flange, ring modulation, etc.)

Eventide TimeFactor (delay and delay-related effects; I use ducking delay the most)

The output from this chain is sent to a K-Mix mixer (by Keith McMillen Instruments) with send/return routing to two double loopers and the second delay:

Pigtronix Infinity (double looper 1), with rocker pedals to control input and feedback levels

Pigtronix Infinity (double looper 2), with rocker pedals to control input and feedback levels

Source Audio Nemesis (delay; I use the ping pong effect most)

The composite mix from the K-Mix mixes then goes through the TC Electronic Hall of Fame (reverb) before being routed out to headphones and house speakers, and recorded using Logic Pro on a MacBook Air.

On stage, performance ready. (The Rotunda, Philadelphia, PA)

Credits

All music composed, performed and edited by Steve Bowman.

Cover art: Steve Bowman

Mastering

Mastered by Saso Puckovski at Earworm Studio in [??]